neumes

Neumes do something different than encoding a theoretical tone system to alphabetical letters. This difference is still visible to us today if we compare a melody notated in standard staff notation with its ‘equivalent’ notated using note names, say ‘E A G# A’. Our staff notation, as well as the neumatic notation, makes use of our metaphorical understanding of high and low tones, representing tones at their respective height on the staff. In Carolingian times, this metaphor was still a novelty and the neumes were indeed the first notational symbols for music which made use of this new conception.

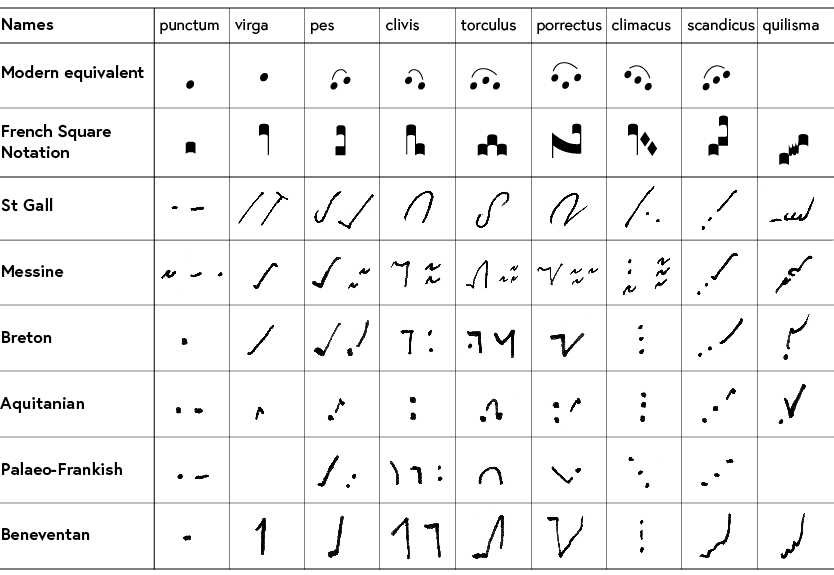

It is important to note from the start that many neume varieties (but not all of them) contain no information about exact pitches or intervals, but merely about lower and higher notes in a musical context. These neumes are called adiastematic neumes, whereas those varieties that actually show us intervals and pitches are labelled diastematic. The simplest neumes were the punctum (Latin for point, dot) and the virga (rod). Both denote single, discrete pitches, punctum standing for a relatively low, and virga for a relatively high tone. Pes (foot, step) is a two-note neume denoting a step up, while clivis (hill) indicates a step down. Our table continues with all possible melodic movements of up to three tones and names the neumes. Quilisma is the only so-called ornamental neume we included in our table as it occurs quite frequently. While the exact meaning of the sign is unclear, there is reason to believe that it stands for a special, tremulous quality of the voice. The names of the neumes we use today are mostly shown in neume tables which start to appear in the 12th century, so they came into use several hundred years after the first neumatic notations had emerged.

As you can see in our table, we can hardly speak of ‘the’ neumes. Although we chose to show only a small selection of the regional varieties of only the most frequent neumes, you can already discover a lot of differences. Sometimes we find different signs for the same melodic movement even within the same neumatic ‘dialect’. This already gives us an idea of how much differentiation was possible in neumatic notations.

In this context, please also note how certain regional varieties sometimes use their own symbols for neumes signifying several tones and sometimes simply write combinations of punctum neumes. For example, the neumes of St Gall never divide pes, clivis, torculus, and porrectus into discrete steps, while several French neume varieties regularly do so (Messine, Breton, Aquitanian). Some neumes, as the ones from St Gall, therefore represent high and low in a rather symbolic manner, while others seem to indicate directly on the parchment how the melody moves – similar to our modern notation. Some varieties, like the Aquitanian or the Beneventan neumes are in fact placed on the parchment in a relatively exact way, so that intervals can be recognised – these are called diastematic neumes.

As you can see in our table, we can hardly speak of ‘the’ neumes. Although we chose to show only a small selection of the regional varieties of only the most frequent neumes, you can already discover a lot of differences. Sometimes we find different signs for the same melodic movement even within the same neumatic ‘dialect’. This already gives us an idea of how much differentiation was possible in neumatic notations.

In this context, please also note how certain regional varieties sometimes use their own symbols for neumes signifying several tones and sometimes simply write combinations of punctum neumes. For example, the neumes of St Gall never divide pes, clivis, torculus, and porrectus into discrete steps, while several French neume varieties regularly do so (Messine, Breton, Aquitanian). Some neumes, as the ones from St Gall, therefore represent high and low in a rather symbolic manner, while others seem to indicate directly on the parchment how the melody moves – similar to our modern notation. Some varieties, like the Aquitanian or the Beneventan neumes are in fact placed on the parchment in a relatively exact way, so that intervals can be recognised – these are called diastematic neumes.